Love and Terror

Handcuffed and shackled at an Israeli military court hearing in January, Yusra Abdu awaits her fate under the ENTRANCE FOR DETAINEES sign.

Yusra Abdu's mother and father had no idea what their 17-year-old daughter was planning, or if they suspected something, they're not letting on. In the Palestinian West Bank, surrounded by Israeli soldiers and steeped in a half-century of warfare, it is not always wise to say what you know. To hear them tell it, Yusra is as wonderfully frivolous as teenagers come, a girl obsessed with music and fashion, a girl who "if you bought her a new dress every day, she wouldn't say no, " her grandmother tells me one afternoon in the chilly four-room apartment the family shares.

All evidence seems to support this view, beginning with Yusra's overfull closet, whose doors are layered with posters of handsome Arab pop stars. And in her empty room, there are the many pictures of Yusra herself, an apparently happy girl whose quick eyes, optimistic smile, and velvety skin helped her seem older than her years and made her the talk of the covered alleys and crooked sidewalks of the Casbah, an ancient neighborhood in Nablus, the 4,500-year-old city an hour north of Jerusalem. In a hidebound world, she is a bright exception - an impression further enhanced by her name, Yusra, a word, taken from the Koran, that means "prosperous."

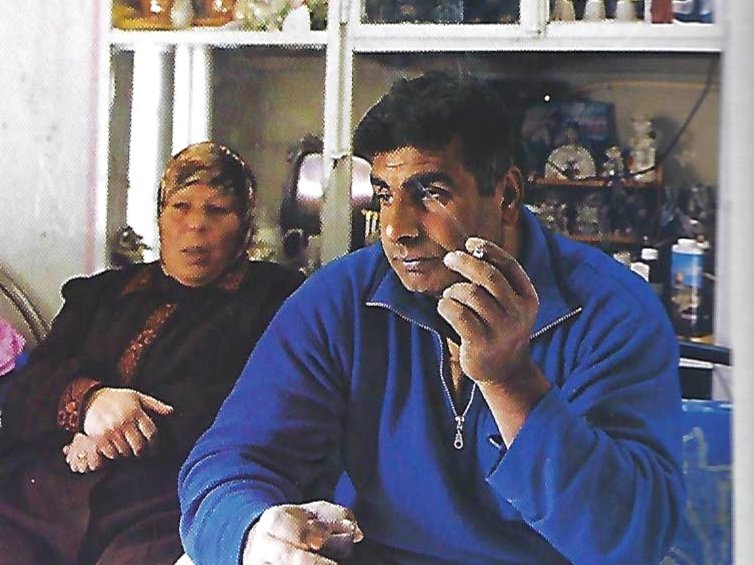

“SHE IS INNOCENT,” insists Yusra’s mother, Samar (left, in her daughter’s old room; above, with husband Mahmoud). Yusra wanted to be a wedding photographer, the couple says, not a terrorist.

"She is a normal girl," Yusra's mother, Samar, protests. "Like any other girl."

That is, like any girl in a part of the world defined by seething hatreds and tragically stymied expectations —what Carol Bellamy, former executive director of UNICEF, calls the obstacles to childhood.

Since January, when Palestinians elected Mahmoud Abbas their leader, talk of peace has gained new momentum on both sides. But nobody thinks it will be an easy transition. After decades of war, most Israeli children say they've never met any Palestinian youngsters; their perception of them have been created largely by media accounts of stone throwers and suicide bombers. Palestinian kids, meanwhile, report that the only Israelis they've ever encountered are young soldiers conducting bloody military operations. As a result, children on both sides tend to view one another as caricatures of evil who delight in killing innocents.

"It's important to convey how deep in the marrow of their bones this is," says Jerrold M. Post, MD, director of the political psychology program at George Washington University and an expert on Middle East terrorism. In 2002 a Tel Aviv University survey found that 40 percent of Israeli and Palestinian youths living in the most violent areas saw no reason to return to peace negotiations.

The past four and a half years have produced considerable hardships on both sides. Occupying soldiers have surrounded most Palestinian cities and villages, regularly declaring round-the-clock curfews, closing schools, and blocking all traffic, including ambulances and vehicles conveying humanitarian aid — a practice human rights observers say has caused dozens of fatalities. Nearly half the families live below the poverty line, defined here as earning just $2.1 a day, and deaths of children — from military and other causes — increased by almost 25 percent last year, UNICEF says. Since the fall of 2000, according to Amnesty International, more than 600 Palestinian kids have been killed, mostly as a result of "deliberate as well as reckless" shootings by Israeli soldiers or shellings of densely populated residential areas.

In Israel, violence is never far away, either, despite advantages in economics, healthcare, and education. Communities are surrounded by razor wire and under the constant threat of terror attacks, which by the start of 2005 had claimed the lives of more than 100 children who did nothing more than climb on the wrong bus or step into a coffee shop targeted by a suicide bomber. When they reach 18, Israeli boys and girls alike are drafted and dispatched to war zones often only a few miles from their homes. The images they see there will undoubtedly taint their whole lives. Even being a pacifist does not ensure a child's safety. Smadar Elhanan attended her first peace rally at age 5 and wrote an antioccupation op-ed before turning 10. But the suicide bomber who approached her and her friends one afternoon in 1997, ending her life at age 14, would never know this.

"You just wonder how every day you can get up and go about your life," says Bellamy after a recent tour of Israel and the occupied Palestinian territories. "The conditions are so strained, you can see how violence might present itself as an option."

So perhaps it was not surprising that last summer Yusra fell in love with Hani Akad, the most dangerous man in town, a handsome 24-year-old who, as everybody in Nablus knows, was the top guy in the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine, one of the armed factions. They never dated. He couldn't date. He was a "wanted," targeted for assassination by the Israeli Defense Forces, unable to move around during daylight hours or sleep in the same bed twice. To many local supporters, he was a freedom fighter who battled the occupying army. To Israel he was a terrorist and an explosives ex-pert. "Hani Akad was a bad guy," an Israeli security spokesman who insisted on anonymity told me, "really deeply involved in teror attacks, organizing and planning them."

HANI AKAD, 24 (left), WAS A WANTED MAN IN Israel, but to a West Bank girl like Yusra (above), he was a heartthrob. “I want to become a suicide bomber,” she said by way of introduction. He asked her if she had patriotic motives. “I told him, ‘No, I’m just bored with life.’”

Nonetheless, Hani reciprocated Yusra's love. Last July he asked her to marry him, and she accepted. If they celebrated this occasion, the joy was not to last. What unfolded over the next few weeks is a desperate tale of crossed signals, betrayal, and disastrous consequences that ended last September, when Hani Akad was killed in a massive Israeli army operation. Wrapped in the Palestinian flag, he was carried to his grave on the shoulders of 10,000 of his compatriots, as local news videotapes attest. And the alleyways that abut his family's home in the Casbah are now plastered with hundreds of full-color posters of a defiant young "martyr" in his glory, cradling his weapon. In death Hani Akad has become a strange sort of icon, as venerated — and as elusive — as the pop stars on Yusra's closet doors.

And since then, Yusra Abdu has been locked up in Israeli custody, charged with planning to become a suicide bomber, an allegation her family vehemently denies.

"These are the most beautiful days of her childhood, and now she is in prison," Yusra's father, Mahmoud Saber Abdu, tells me as tears stream from his honey-colored eyes. "She is just a child."

His wife corrects him. "The Palestinian does not have a childhood," Samar says sadly. "Not in these circumstances."

In the 1980s, when suicide bombings first made headlines, psychologists tended to label the perpetrators as mentally unstable religious fanatics. But today scholars agree that most are otherwise ordinary people whose ready passions and chronic disappointments make them easy recruits for larger political powers. "What people miss is the fact that religion is not the cause; it's the context," says Georgetown University professor of Islamic studies John L. Esposito, PhD, author of Unholy War: Terror in the Name of Islam. Esposito offers another explanation — though not a justification — for what motivates bombers. "These are people who define their situation as hopeless. They feel that they have no way to respond against what they see as Israeli military aggression. They say, ‘They have weapon on that side, and [we have] none on our side.’ So they turn themselves into weapons."

Since 2000, 147 Palestinians — eight of them women — have undertaken suicide bombing missions in Israel, killing at least 500 and injuring more than 3,000, the vast majority of their victims civilians. And the number of female recruits is growing at an alarming pace. Of the estimated 67 women believed by Israeli security forces to have conspired to become bombers, most did so last year. Eleven of them were under 18.

What would make a girl take such a radical and grisly step? Some experts suggest that while these young recruits are politically motivated, it takes a highly personal turn of events to push them over the edge — a divorce, a broken heart, the violent death of a loved one. "I have a bunch of young [Palestinian] women clients who experienced difficulties with their private lives, and then — how shall I say it? — the ‘patriotic solution' seems to be the correct one," says lawyer Leah Tsemel, a well-known Israeli defender of Palestinians. Demand is also a driving force, according to Isobel Coleman, director of the Women and U.S. Foreign Policy Program at the Council on Foreign Relations in New York City. Women and children, she says, have a better chance of making it past Israeli checkpoints with their payloads than men do.

Hoping to make sense of this disturbing trend, I began appealing last spring to Israeli government officials to let me talk to one of the girls accused of plotting a suicide attack. The Palestinian Authority believed that at least four were being held for bomb-related crimes, most in adult facilities. For months my quest was frustrated, first by an official bureaucracy that is suspicious of the foreign press and later by a new stance adopted by Palestinian inmates to shun all interview requests.

Yusra Abdu's name appeared on a list of newly arrested Palestinian bombers provided to me last fall by the Israeli domestic security agency, Shin Bet. They interrogated her for three weeks before extracting a confession, they say. I chose her at random, an anonymous young Palestinian girl whose life had wended toward violence. She is undoubtedly a fleeting footnote in the long history of Middle East conflict, and her story cannot settle for Palestinians and Israelis the profound debates over terrorism and freedom. But understanding the bad decisions made by one girl, I hoped, might suggest a way to stop others from taking the same path — in other words, might help save lives.

I had no idea if she would agree to talk. At the time, I knew none of the particulars of her surprising story.

It was cold and damp on the December morning I visited the cramped apartment where Yusra has lived since she was born on April 16, 1987, the first child of Mahmoud, now 41, and Samar, 37. Her mother and grandmother, along with number of other women, sat in winter robes and tight Islamic head wraps, warming their hands around cups of tea. Layers of carpet on the floor did little to take away the chill; there was no central heating. A small bird in a cage hung high on the wall sang occasionally, the only suggestion of cheerfulness in an otherwise grim home. Mahmoud arrived shortly from his job as a day laborer, muscling heavy loads through the city streets when he can find the work.

The couple, both followers of Islam, describe themselves as not very religious or ideologically engaged. They have tried to steer clear of the violence around them. "No one wants to be occupied; we are under siege forcefully," Mahmoud explains, echoing what has been declared in a series of UN resolutions and accepted by the United States and most international legal authorities, despite arguments to the contrary by the Israeli government. "But I brought my children up to value life."

"She was a good student," Samar tells me, producing various certificates her daughter earned — one for working as a first-aid volunteer for the local EMS, another showing proficiency in Microsoft Word, PowerPoint, and related computer applications. "She scored 95," Samar says proudly, pointing to the computer-course diploma. It was photography, however, that inspired Yusra. Her dream was to become a professional wedding photographer.

"My family is a family that likes peace," Samar says.

But peace in the Middle East is in extremely short supply. Seeds of the current intifada were planted in July 2000, when carefully tended peace talks fell apart following a summit at Camp David. Critics blame both sides, accusing Israeli leaders of offering concessions they knew Palestinians would not accept, and faulting late Palestinian leader Yasir Arafat for abandoning the talks, which held the promise of an independent Palestine, without making a counteroffer. Tensions exploded two relatively quiet months later, on September 28, 2000, when the right-wing Israeli leader, Ariel Sharon, paid a visit to one of the holiest places in the Islamic world, the site of the Dome of the Rock mosque in the Palestinian section of Jerusalem. Sharon has never fully explained his reasons for showing up with 1,000 police officers in riot gear just as Muslims were gathering for prayers. Angrily, the people poured out of the mosque, and the ensuing clashes over the next few days left at least a dozen Palestinians dead.

In the following weeks, rioting spun out of control, Palestinian youths across the region, already brimming with resentment over the fact that the decades-old peace process hadn't brought them any relief, reacted by hurling stones and Molotov cocktails at the Israeli army encampments surrounding the entrances to their towns. Firebrands called for all-out war against Israel. Palestinian leaders, perhaps powerless to contain the uprising, made only passing efforts to stop the violence, while Arafat often seemed to incite it. In an interview broadcast on local television in 2002, he offered a message to Palestinian children. "This child," he said, "who is grasping the stone, facing the tank, is it not the greatest message to the world when that hero becomes a martyr? We are proud of them."

The Israeli crackdown since 2000 has been overwhelming. Entire cities at times have been sealed off interminably; infrastructure such as electricity grids and roads routinely interrupted or destroyed. According to the United Nations, more than 2,500 Palestinian homes have been damaged or razed in what the Israeli army calls clearing operations, leaving 23,000 homeless. And at least 25,000 Palestinians have been arrested, other sources report. Israel justifies these maneuvers by saying they were necessary to reduce the number of suicide bombings, which spiked in 2002 and have declined dramatically since. Nonetheless, a poll taken in 2003 showed that 55 percent of Palestinians still favored suicide attacks against Israel, and only 27 percent opposed them outright. "Every Palestinian today is a potential suicide bomber, as far as we see it," says Major Sharon Feingold, a spokesperson for the Israeli Defense Forces. "For us, no one is innocent anymore."

Amnesty International has accused both sides of targeting minors, a war crime under the Geneva Conventions. In a UNICEF-supported survey of Palestinian children conducted last November, one in four said their schools had been fired on or shelled. "They're totally distressed," says Anne Grandjean, psychosocial officer for UNICEF in East Jerusalem. "In study after study we see the results — bed-wetting, nightmares, low achievement in school."

No city has experienced the crisis more acutely than Nablus — which has produced more suicide bombers than any other municipality, according to the Israeli army-and no neighborhood more than Yusra's. Movement on the streets is difficult and risky, and employment is rare, her uncle Ayman Mustafa Kulab tells me. A few days earlier, he says, he tried to travel I5 minutes south for work but was detained for three hours at a military checkpoint. Eventually denied passage, he was forced to return home. "I did nothing wrong," he says. "This is the kind of pressure they have us under."

Last year, in seemingly random events, the violence struck Yusra's family twice. In January one of her uncles was shot nine times from an Israeli sniper nest as he walked to work, the family says. Amazingly, he survived. Then last June, a lengthy military curfew required them all to stay inside the apartment, keeping them from buying food or going to work. The lockdown came during a crushing heat wave. The family says that after darkness fell on the 14th day, they sneaked onto the roof, hoping to cool off. They had heard of others who had tried this. "It was prohibited, I know, but it was so hot," Samar says. "We couldn't stay inside another minute." They had been up there only a short while when a sniper's bullet caught Yusra's little brother Tarik, 16, in the wrist. Then three more bullets tore into him, one opening the artery in his left leg. In the bedlam that followed, he slid off the roof and fell four stories into a deep pit between two buildings.

He survived, although even after four surgeries it is not clear if he will ever be able to walk without assistance. His injury traumatized the family and pushed them further into financial ruin. "I can't work now," Tarik says, rapping with a knuckle the cast that runs the length of his leg.

Yusra's relatives worry that these events may have set her on a path of radicalization. "When her brother was injured, she went crazy," Samar says. But she contained her anger, Mahmoud adds. "When she saw him bleeding, she was afraid. And she was sad. She didn't think about revenge. She thought about Tarik."

This may be so. In notes from her interrogation, however — a copy of which was given to me on the condition that I not reveal how I got it — Yusra doesn't mention her brother's wounds. Perhaps it was simply a coincidence that around that time she first laid eyes on Hani Akad in the Casbah, when his fiery glance and dimpled cheeks caught her attention.

"He used to come to the neighborhood and visit the son of our neighbors," she said in the statement. When she heard the boy call the visitor Hani, she knew that this was the legendary Hani Akad, who was on Israel's most-wanted list. According to her statement, Yusra approached him in the neighborhood and introduced herself with a most improbable line: "I want to become a suicide bomber." She told her interrogators, "Hani asked me, 'Do you have patriotic motives?' I told him, 'No, I'm just bored with life.'"

By any measure, boredom is a bizarre motivation for contemplating such an awful undertaking. Even Hani was dismissive. "He started telling me, 'We don't send young girls, or girls at all,' and I told him, 'No, I want to go!'"

Yusra's family insists that none of this can be true. "She tells me everything," says Shoroq Kulab, one of her best friends, "and she never mentioned anything like this." Yusra's wounded uncle thinks her Israeli interrogators put those words in her mouth, "She has never talked about politics. Whenever she heard about suicide bombings, she would always say, 'Oh my God. Why? Isn't it forbidden for the Israelis to be killed in such a way?' Because her brother and uncle worked inside Israel, she worried that they could be victims someday of these Palestinian suicide bombers."

Perhaps on the miserable streets of Nablus, offering to enlist as a suicide bomber was a young girl's way of flirting. If so, apparently it worked. A romance blossomed, and the subject of suicide never came up again. The pair didn't have the luxury of holding hands in the park, though such behavior would not have been permitted by local mores. Instead they would visit her brother in the hospital together, her family says, and steal other opportunities to socialize. In her statement, Yusra said Hani proposed to her in the summer of 2004. Though she was just 17, she accepted. "He asked my parents for my hand, and I loved him, not because he was wanted but because of who he was. I used to ask him to turn himself in, and he told me he couldn't."

HANI AKAD, THE SECOND OF FOUR children, lost his father when he was young, his mother tells me. She invited me to her sparsely furnished apartment one day in December for a small glass of Arab coffee flavored with cardamom an to watch a videotape of his funeral that friends had made and that she confesses she plays obsessively. The rooms were nearly empty and the floors were bare, making for a heavy echo. In the middle of the living room was a small kerosene-powered radiator on wheels, the only source of heat in the apartment. Like Yusra's mother, Basma Akad sat with a stack of photographs in her lap. Many of them captured her son posing with an arsenal of weapons — chiefly a menacing M-16 rifle — but in others he could be any high school senior, beaming or pouting for the camera, hands stuffed deep in the pockets of his jeans. Despite the supervision of uncles, aunts, and cousins, or maybe with their overt approval, Hani was drawn to the conflict that flared around him. "From the time he was very young," Basma tells me, "he was throwing stones at the Israeli soldiers. He would take car batteries —from the soldiers' cars — connect them with electrical wires, and put them in the middle of the street to make the Israelis think there was an explosive. He would go to the roof of the house to see their reactions. He was very happy to see them afraid."

A spirited woman in formal robes, she speaks of this troublemaking with pride, but she also says she tried to stop it, without success. Then in April 2002, Israel mounted a sweeping invasion of Nablus in pursuit of suspected terrorists, destroying homes, cutting power to an estimated 47 percent of the city, and interrupting essential services. The siege lasted more than two weeks, left many dead, and threw the city into chaos. As a volunteer with a first-aid agency, Hani was allowed to cross firing lines to remove injured townspeople once Israelis deemed it safe. This put him in a position to see the extensive damage around town, sights that put a flame to his anger, Basma says. Israeli soldiers talk about a similar hardening when they take in the twisted aftermath of a suicide bombing.

"It was then," Basma tells me, "that he started to deal a lot with the wanteds. He started to deliver their weapons from place to place. If someone was injured, he would go to sleep with them in the hospital. Sometimes he would bring them here to sleep. He felt pity for them."

Soon he picked up a weapon and joined the insurgency. Within months he rose through the ranks of the Democratic Front — an offshoot of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine — which, though violent, has never produced a suicide bomber, according to Israeli government sources. "He bravely fought the occupation and helped many of the boys," says Basma, and she repeats her son's claim that he killed five soldiers in battle, never a civilian. "But I'm still a mother. He's still my oldest son. Sometimes I told him to surrender: They'd imprison him and eventually release him, and he'd be able to live like any other guy. He used to say, 'If I still have blood in my body, I will go on carrying my weapon to resist occupation.'"

Han learned in December 2002 that he had become a wanted. Over the next two years, his mother hardly saw him. He slept in a succession of safe houses, mostly in the Casbah, and communicated with her by sending text messages to her cell phone. When his sister married, Hani listened in on the ceremony on his phon and made a lightning-fast visit to the banquet hall, bearing a wedding gift. "They cried together, and he left running," Basma recalls.

These constraints must have created a serious obstacle to his romance with Yusra Abdu. His mother was aware only of the meetings they stole while visiting Yusra's injured brother. She went to one herself, to get to know the young girl. She also met Yusra's mother there. Basma says she opposed the wedding, not because of any flaws in the bride-to-be but "because he was wanted, that's all. I didn't want anybody's daughter to live in that kind of hell."

"Was she a militant?" I ask Basma.

"No, not at all," she answers swiftly. "I've never heard her name. Hani used to talk about his friends who were military, but he never mentioned her or her family. I was surprised to hear she was arrested." According to the indictment against her, however, Yusra met early last September with a man named Nader Aswad, local head of the extremist Al Aksa Martyrs Brigades, which are responsible for some of the worst suicide attacks against Israel. She allegedly offered him her services as a suicide bomber, just as she had done a few months earlier with Hani. This time she seemed more determined. "She was prepared to blow herself up in a suicide attack in Israel," an Israeli law-enforcement official tells me. The recruiter allegedly sent her home to pray and await further instructions.

Her parents can't believe this is true. They point out that she had a busy agenda at the end of August and the start of September, signs she wasn't expecting to die. There was a birthday party for a relative and a friend's upcoming wedding, both of which she had promised to photograph. She had her teeth fixed and got into a fight with her brother for trying to poach her chocolates. "She was innocent," her mother insists. "A girl who quarrels about such small things can't be planning such a crime!"

Besides, as far as anybody knew, she had her own wedding to look forward to.

Whether or not yusra was planning a suicide attack, the inescapable truth is that she and her fiancé were born into a world that venerates as a hero any Palestinian who dies in the conflict with Israel — in pitched gunfights, from a stray bullet, or as a suicide bomber. Everybody agrees that there are more willing bombers today — including teenage girls — than there are bombs. A few promising efforts to change this dark dynamic are underway. Every summer Seeds of Peace, a New York-based nonprofit agency, brings together more than 300 Arab and Israeli teenagers to get to know one another "before fear, mistrust, and prejudice blind them from seeing the human face of their enemy," as the group's literature declares. On a larger scale, UNICEF has funded 100 summer camps that reach 10,000 Palestinian children every year, teaching conflict resolution, team building, and crosscultural respect. (Because the UNICEF charter limits the places where the organization may work to impoverished nations or regions, it does not operate inside Israel.) In addition, UNICEF has helped build eight well-marked and fortified "safe-play areas" in the hardest-hit sections of Gaza and has financed local hotlines and psychosocial programs for children suffering from trauma and stress.

"We try to show up immediately after an incursion and respond in whatever way we can," says UNICEF's project officer in Gaza, Joachim Paul. "We can't protect the children from the violence, but we can try to help them feel safe again afterward." In an intervention program UNICEF supports in Gaza, a sixth-grade boy named Muhammad was being given special care because his reaction to a recent missile attack had caused alarm. He had danced down the streets of his refugee camp, right through the scattered remains of a man in the road. "I saw pieces of body everywhere; I helped collect them," Muhammad tells me, pantomiming how he pinched scraps of flesh between his thumb and forefinger and waved them about. "This is common," a local reporter, Taghreed El-Khodary, tells me gravely. "They're becoming like wild animals, these little kids."

Girls may have a less explicit response, but their trauma is just as deep. Nine-year-old Heba Zourob, who lives in Khan Younis, a southern Gaza refugee camp, was playing in the schoolyard with other students last December 12 when Israeli mortar fire hit the playground and severely wounded seven of her classmates. It wasn't until they'd been rushed to the hospital and classes had resumed that Heba realized a piece of shrapnel had lodged in her own small shoulder; shock must have masked her pain. More hours passed before anybody noticed she was still gripping a sandy piece of candy she was about to eat at the time she was wounded.

"I pried it out of her hand in the hospital," her mother tells me two weeks later. "Now she has started wetting her bed at night. Last night I changed the bedding twice." Heba is undergoing the UNICEF-financed crisis counseling as well. Experts applaud the programs, but few people feel they will be enough to erase the motivation behind suicide bombing, even as talks of peace have made meaningful strides for the first time since 2000. "We believe that political peace processes are of course important, and we support any negotiations," says Gon Kafri, director of development at Parents Circle, a grassroots group of bereaved Israelis and Palestinians who have lost family members in the conflict and now try to promote peace. "But we [also] believe that without dealing with the people themselves and establishing in them the possibility of reconciliation, no peace agreement will be sustainable or lasting." Acting on this philosophy, Parents Circle launched a unique telephone service that allows Israelis and Palestinians to press *6364 on their home telephones and be connected with someone on the other side. The peace group had no idea whether anyone would even attempt a dialogue. But in the two years since then, about half a million calls have been placed, and many people using the system have become friends. "They might start shouting," Kafri says, "but if a person bothers to pick up the phone and dial to another person, even if he starts cursing, it doesn't end there. He broke the ice and found a human being… and the effect is incredible."

On a rainy morning this january, four months after Yusra Abdu's arrest, a swarm of soldiers usher her into a military courtroom in the northern Israeli city of Salem. In contrast to her appearance in the photos I've seen, she is wearing traditional Islamic garb — a brown prison-issue headscarf and jacket over a floor-length brown dress. But beneath the hem, I notice that she is also wearing bell-bottom blue jeans and platform shoes, irrepressibly fashion conscious even with her ankles looped together in leg irons.

As she shuffles carefully across the room to her seat at the defendant's table, she waves at her weeping mother and grandmother in the gallery, who have made the long journey to see her, and calls out reassurances until the military judge issues a stern warning.

The purpose of her appearance is a reading of the charges against her, a formality that takes slightly more than a minute. Afterward, by arrangement with her attorney and military officials, the soldiers escort her into a spare room where I'm allowed to ask her for an interview. At the last minute, they tell me I can't use my own interpreter, saying he might be "biased," and they force me to pose my questions through two armed soldiers — one who will put my words into Hebrew, and another who will turn them into Arabic. Her replies will be bobbled back through the same channels.

While all this is being worked out in Hebrew, Yusra and I are unable to communicate. Instead we stare at each other. She does not seem intimidated by the chaos or uncomfortable in her tight handcuffs. In fact, she smiles at me. "Yusra," she says in a high voice, pushing an index finger to her chest — a simple gesture to suggest that she was expecting me. I introduce myself similarly, and she nods hello.

So much of her story confuses me. Why did she bring up suicide attacks when she first spoke to Hani, I ask her when the bickering among the soldiers dies down. She giggles, and for the first time I see her as a bit of a coquette.

"I said I would undertake a suicide mission, but only in order to get close to him," she tells me. "Because he was preoccupied with such matters."

"Then you never thought about actually doing it?"

Her smile vanishes. "Not in the beginning," she says carefully. "Then some things happened that led me to change my mind." Early last September, she explains, Hani sent an emissary to break off their engagement. This is surprising news to me. Her family may not have been aware of that development, as they never mentioned it. "I was astonished," Yusra tells me, her dark eyes growing moist. "I really wanted to know why." The emissary had no explanation to offer.

A few days later, Yusra made contact with the 28-year-old Nader Aswad. In her written confession, she said she bumped into him by chance. She demanded to know where her former fiancé was hiding out. Nader didn't tell her. Instead he gave her his own cell phone number and instructed her to call him the next morning, when perhaps more information would be available. The following day, she did as she was told, phoning him from the office of her dentist. Nader said he needed to see her urgently and rushed to the dentist to find her.

He wasted no time. He said, "I ask you to do a suicide mission," Yusra related in her statement.

The date was September 9, 2004, an apex of tensions in Nablus. Israeli forces had just begun staging a series of surgical raids in the occupied territories that would leave dozens dead. A day later, they would seal off the West Bank and Gaza for the extended Jewish New Year festivities, severely limiting the movements of more than three million Palestinians. Simultaneously, Arafat's health was in serious decline, sending clouds of uncertainty over the territories. But Yusra was not moved. She refused Nader's request, she claimed.

"Then he told me, 'Your fiancé is going to do a martyr mission,'" she stated.

Now she had an explanation for their breakup. She asked when the mission would be carried out, but Nader was evasive. "Everything has its time," was all he would say.

In a sudden Shakespearean twist, Yusra changed her mind. She agreed to his re-quest, not with the brio of an avenging terrorist but with the resignation of a brokenhearted girl. But, she stated in her confession, "I told him to postpone the mission for now because my mother was sick. I wanted to find out if my fiancé, Hani, wanted to go for a suicide mission or not."

The next day, Hani showed up unannounced at Yusra's house, his first visit since sending the messenger to break off their engagement. It seems he had heard about her martyrdom pact and had come to talk her out of it. From her, he learned what Nader was saying about his own intentions to carry out a suicide attack. It was not true, Hani told Yusra. "Nader tricked you," he reportedly said. This dovetails with what Han's mother told me. According to her, Hani found out in early September that the Israeli army was planning an operation in which he would likely perish. She says he learned this when his archnemesis, an Israeli officer whom Basma knew only as Captain Namrud, called his cell phone and made it plain that Hani had run out of hiding places. Hani phoned his mother to prepare her for his death. His intention was to die in battle with soldiers, she says.

Then he broke off his engagement. He wanted to soften the blow of his impending death, Basma told me when I visited her. So he decided to convince Yusra that he never loved her in the first place, hoping her anger at him would make her less likely to seek revenge on the Israelis or become targeted by the army, Basma says. "In order to not have her entangled in this, he just sent a friend to say, 'I don't want to marry you.'"

The ploy backfired terribly. Yusra would not accept the breakup. She had a friend call Hani's mother to beg for her intervention. "I told her he could not marry," Basma says. "He used to say, 'My weapon is my wife, and my wedding is my martyrdom.' But this girl told me, 'Yusra is ready to die. Yusra said, "If he is going to die, I'm ready to die also."' I told her, 'God only knows what the future might hold.'"

During Hani's surprise visit, Yusra agreed to withdraw her consent to the suicide mission, according to an Israeli military source with access to intelligence information, only after he once more asked her to marry him. But later, after Hani called Nader to relay this, Nader "began to threaten her and said he would shoot her and tell people in the village that Yusra was a collaborator with Israel," says her defense attorney, a soft-spoken man named Mohammad Naamnah. Hani and Yusra both argued with Nader. The intimidation was intense.

"Despite that," Naamnah says, "she did quit."

On September 13, at 2 in the morning, Yusra's parents say, 100 Israeli soldiers in 30 armored vehicles surrounded their home. In her fright, Samar assumed they had come for her son Tarik, but the voice rattling through the apartment door was unequivocal: "Where is Yusra? I want Yusra!"

According to Samar, the man at the door was Captain Namrud, the same Israeli officer who had called Hani's cell phone. Though it is not clear how the soldiers knew what Yusra was planning, it could be that Namrud had monitored their love affair over cell phone calls. "If you use the mobile to talk to people in Nablus... well, you understand this is the source of information for the Israelis," says Yusra's attorney. "In addition, it is well known that there is a vast network of collaborators in the cities. The Israelis have been very successful at this."

The soldiers knotted a blindfold over Yusra's eyes and roped her wrists together before walking her out of the house in her pajamas. She joined 340 other Palestinian minors in Israeli jails, 69 percent of whom were there for throwing stones or associating with organizations banned by Israel, according to the Palestinian Authority. She signed her formal statement in her third week of interrogation. Its last lines read like a plea for a fresh start: "I really, really regret what I said. I thank God I didn't do anything. For the love of God, I want to live like any other girl. I want to finish my studies. My parents need me to be at home."

Yusra's military prosecutor, Captain Raid Shannan, acknowledges that she never handled explosives and, in the end, didn't intend to follow through on a suicide mission; but merely by consenting —first flirtatiously, later under coercion — she crossed the line. Shannan considers her an ongoing danger to the state of Israel. "I think she has the background to do this thing," he says. "Her family, or village, or neighborhood, or city — maybe they all encouraged her. It's not unusual that you have girls in that region who want to do these things." Yusra is charged with one count of conspiracy to commit willful manslaughter, for which she could receive up to seven years, says a West Bank-based lawyer for Defense for Children International, Khaled Ouzmar. "We're seeing a number of cases like this — where initiating a conversation is enough to be arrested and accused. We have never had this before."

Two days after Yusra's arrest, right after morning prayers, Hani called his mother on his cell phone and muttered an Islamic benediction, Basma recalled.

"He said, 'We are surrounded from all sides; I'm going out to confront them.' I begged him, ' Just surrender. Don't go and confront them!' He didn't answer me —he just turned off his mobile phone."

An hour later, with Nablus still in pre-dawn darkness, Hani called Basma again and said he had been wounded and his guns had been emptied in battle. Things did not look good. "Ask God for forgiveness," he said.

"You have to surrender," she pleaded. "You have nothing to fight with!" But his phone went dead. She redialed his number over and over, into the first light of day, but he never answered again. "I knew then that he was dead." she said.

The news reached Yusra on the prison radio. "I was very upset," she tells me in court that day.

"Did you cry?" I ask.

"Oh, I cried," she says, glancing sadly at her handcuffs.

At that moment, the soldiers abruptly end our interview, rustling Yusra to her feet and leading her toward an armored van for the trip back to prison. But there's something else she wants to say to me, something the soldiers aren't translating. "What is it?" I demand of one of the translators, an 18-year-old private who learned perfect English by reading American novels. "What is she saying?"

The two of us watch the chain swinging between her ankles as she shambles away. I can't help thinking how old she looks at 17— her childhood gone and her future imperiled, for all I can tell, because of a girlish crush. "She said, 'I loved him very much,'" the soldier tells me finally. "She said, 'Yes, I cried a lot. I cried for two months.'"

Later, in the car, the soldier says he believes she was telling the truth. Given the long mutual distrust between their communities, I'm startled: Does that mean he doesn't view Yusra as a threat to Israel? "Is she a terrorist?" I ask.

"Sure," he says easily. "She did talk about it twice."

"But she says she never intended to do it. Doesn't that make a difference?"

He shrugs, sliding his skinny body low into the seat to make a quick cell phone call to his mom. Though he is deeply embroiled in a war fought by teenagers and young adults, like Yusra he leaves the big questions — of innocence and guilt, peace and war, life and death — to the grown-ups. Whether the grown-ups will finally make positive changes remains to be seen.

As this story went to press, we learned that Yusra received a 15-month sentence.

*This article appears in the June, 2005 issue of O, The Oprah Magazine. © 2005 by David France